Social Mobility and the Failure of Social Democratic Policies in the Western World

Introduction - Understanding Social Mobility

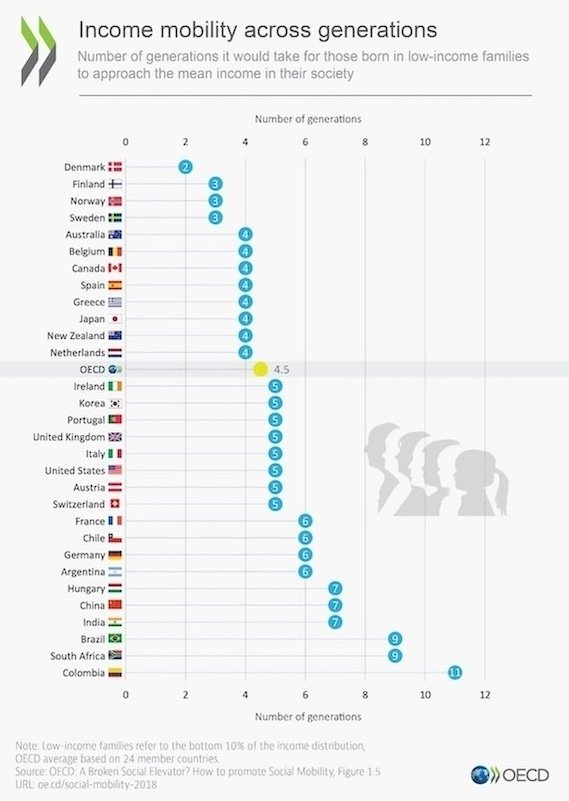

The term ‘social mobility’ refers to a change in a person's socio-economic situation, either in relation to their parents (inter-generational mobility) or throughout their lifetime (intra-generational mobility). The possibility for individuals to improve their social and economic status over their lifetimes is a crucial aspect of a just and equitable society. In the last few years, an increasing scholarly attention has been drawn on social mobility , mainly because Western societies are apparently becoming more immobile, in a context of growing inequalities. Recent contributions have also shown that throughout the last decades, social democratic policies, aimed at addressing this issue effectively, have failed. Civil society is under the same impression , which contributes to fostering unease and political and social instability (1). As usual, anxieties about the present suggest looking at the past for some possible lessons. Taking advantage of the most recent contributions on the topic, this article attempts to acknowledge the reasons behind the stagnation of social mobility in the Western world and explore the shortcomings of social democratic policies in addressing this issue.

Historical context of social mobility in the post-war era

In the West, the post-war period represented a remarkable shift in social mobility, abandoning a system of rigid class structures and providing great opportunities for increased growth. This is confirmed by Nathaniel Hilger (2), who emphasizes the increase in indicators significant for social mobility from 1940. Through a measure of intergenerational mobility developed from census data, Hilger affirms that from 1940 to the end of the 1960s, intergenerational mobility increased dramatically in many Western countries. These post-1940 gains in intergenerational mobility were economically large and were accompanied by sharp increases in social spending and investments in education. In the United States, for example, government spending on education as a percentage of GDP nearly tripled from 2.6% in 1940 to 7.1% in 1970, improving the access to higher education to individuals with disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds.

However, over the past four decades, upward mobility has lost momentum, especially in Western societies, whereas going down the social ladder has become more common. A study by Oxford University with the London School of Economics and Political Sciences (3) tried to unravel the main reasons behind this deceleration by looking at more than 20,000 British people in four birth cohorts from 1946, 1958, 1970 and 1980-84. The co-authors of this study concluded that a possible explanation has to be found in the changing class structure of modern societies. First, from the 1950s to the 1980s professional and managerial employment significantly spread. However, this expansion has slowed down (4), and the children of those who benefited from it through upward mobility now have less favorable prospects than their parents had when they were young. The study also finds that inequalities in the chances of individuals of different class origins ending up in different class destinations have not increased – though neither have they been reduced. Moreover, for men and women alike the inequalities are significantly greater than previously thought – and much greater than if, for example, only income mobility were considered. For example, the chances of a child with a higher professional or managerial father ending up in a similar position are up to 20 times greater than these same chances for a child with a working-class father. Similarly, in the USA, only half of those entering the labor market today can expect to earn more than their parents compared to 90% of individuals born in 1940 (5).

The failed attempts of governments to promote social mobility

But what have Western societies done to improve social mobility? Firstly, it's important to note that improving social mobility is a complex and ongoing endeavor. Challenges such as systemic inequalities, economic shifts, and global dynamics continue to shape mobility outcomes and do not allow policymakers to propose solutions that would suit more static contexts. In recent instances, Western governments have employed multi-faceted methods combining education, progressive taxation, and social welfare programs to promote social mobility and decrease disparities in opportunities and effects within their societies.

According to a number of scholars, enhancing access to quality education is perhaps the most crucial factor in improving inter-generational mobility (6). Western countries have focused on expanding especially tertiary educational opportunities for all, regardless of their socio-economic backgrounds. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, individuals with a bachelor's degree earn, on average, 62% more than those with only a high school diploma, indicating that access to higher education can substantially increase earning potential and economic mobility. The attempt at widening the access to high-quality education meant an increase in funding for public universities, providing scholarships and financial aid for higher education, and implementing programs to address educational disparities in disadvantaged communities. However, these attempts to reform education have resulted in further increases in disparities among pupils and prospective students, in particular when considering the most desirable schools (7). According to John Goldthorpe, a scholar at Oxford University, little has changed largely because wealthier families used their economic, cultural, and social advantages to ensure that their children remain at the top of the social class ladder.

Moreover, these programs alone often fail to reach their targets because of the underlying economic and structural factors that influence social mobility. For instance, the 2021 report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on educational attainment in Eastern Europe has highlighted substantial differences in the quality of education and labor market outcomes between Eastern and Western European countries (8). In some Eastern European countries, despite expanded access to education, individuals may still face limited opportunities for upward mobility due to underdeveloped labor markets and economic conditions.

Throughout the years, Western governments focused also on the geography of the lower social class to tackle issues of upward mobility. A seminal study (9) analyzed upward mobility for every metro and rural area in the U.S. using anonymous earnings records on 10 million children. Through this study, he argued that places of birth have a causal effect on upward mobility for a given person. For example, growing up in one of the bottom 10 counties of the US instead of an average place determines a negative change in predicted earnings of -17.3%. To tackle this issue, Western governments committed to investing in the redevelopment of distressed neighborhoods, especially in metropolitan areas with high levels of immigration and low-income residents. These urban planning interventions, however, have not reached the expected outcomes, mainly because they resulted in increased racial and income segregation, with scarce social capital, limited investments in public infrastructures, and long commuting times from the most productive neighborhoods. Some scholars (10) argued that one of the drivers behind effective housing policies lies in the creation of mixed-income neighborhoods. Historically, creating communities of various social extractions was considered a solution for improving the social position and health of disadvantaged communities in society. This social mix can create several mechanisms to improve the lives of disadvantaged communities (11), among which we can list the promotion of social capital and social interaction among residents, better access to higher quality public and private services and institutions, and decreased exposure to violence. Although these urban policy settings have been applied for almost two centuries, urban redevelopment strategies from Western governments are often targeted at redeveloping or creating neighborhoods just for low-income classes.

Finally, the availability of high-quality public infrastructures has had far-reaching consequences for the social mobility of its citizens. The presence of an efficient transportation system is indeed a critical element that affects social mobility, as it expands job opportunities for individuals, especially those living in economically disadvantaged areas. A study conducted by Chetty and Hendren in 2018 (12) found that commuting time to work significantly affects upward mobility, with shorter commutes associated with better economic outcomes. Therefore, investing in transportation infrastructure can reduce spatial barriers and enable individuals from lower-income backgrounds to access better job prospects. However, the effectiveness of Western governments' policies on infrastructure is often hampered by inadequate planning and oversight. Inefficient project management, cost overruns, and delays can limit the positive impact of infrastructure investments. For instance, delays in the construction of public transportation systems can lead to prolonged periods of limited mobility, which disproportionately affect lower-income individuals who rely on the existing forms of public transit. Actually, infrastructure projects are found to often experience cost overruns and delays due to inaccurate initial assessments and political pressures (13). Such issues can undermine the benefits of infrastructure improvements and so limit or even worse, change the intended effects on social mobility.

Similarly, access to quality healthcare services is crucial in promoting social mobility, as it prevents individuals from falling into poverty due to medical expenses but also to maintain good health, allowing them to participate fully in the workforce. For example, the Affordable Care Act in the United States expanded access to health insurance coverage for millions of previously uninsured individuals and contributed to improved health outcomes and financial stability. However, recent studies indicated that this expansion led to increased healthcare access and reduced financial strain on low-income households (14).

Conclusion

Social democratic policies could still emerge as transformational winners in the fight against declining social mobility. But the clear gap between intended outcomes and actual impact raises questions that require answers. A critical examination of these policies touching several domains has shown their limitations, especially when their action is hampered by inadequate planning and the persistence of structural inequalities within societies. Despite efforts to promote equal opportunities, deeply rooted disparities in education and access to public services still persist, creating barriers that impede upward mobility for disadvantaged individuals. In a nutshell, the aim of Western governments should be to enact far-reaching policies aimed at addressing the foundational issues perpetuating social immobility, while considering the potential short-term consequences on the beneficiaries.

References

Cfr. R. Benabou & E. Ok, “Social Mobility and the Demand for Redistribution: The Poum Hypothesis”, in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), (2001), 447–487; Cfr. T. Piketty, “Social Mobility and Redistributive Politics”, in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(3), (1995), pp. 551–584.

Cfr. N.G. Hilger, The Great Escape: Intergenerational Mobility in the United States Since 1940. Working Paper Series, Issue 21217, 2015.

Cfr. E. Bukodi et al., “The mobility problem in Britain: new findings from the analysis of birth cohort data”, in The British Journal of Sociology, 66(1), (2015), pp. 93–117.

Cfr. E. Bukodi et al., “The effects of social origins and cognitive ability on educational attainment: Evidence from Britain and Sweden”, in Acta Sociologica, 57(4), (2014), pp. 293–310.

Cfr. R. Chetty et al., “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940”, in Science, (2017). Available at: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/early/2017/04/21/science.aal4617.full.pdf.

Cfr. L.E. Major & S. Machin, What do we know and what should we do about...?Social mobility. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2020).

Cfr. L.E. Major & S. Machin, Social Mobility and its Enemies: A Pelican book. London: Pelican, an Imprinting of Penguin Books (2018).

Cfr. OECD/UNICEF (2021), Education in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Findings from PISA. Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/ebeeb179-en.

Cfr. R. Chetty et al., “Where is the Land of Opportunity: The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States”, in Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), (2014), pp. 1553–1623.

Cfr. Chetty et al., 2017; Cfr. I. Levin et al., “Creating mixed communities through housing policies: Global perspectives”, in Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(3), (2022), pp. 291–304.

Cfr. G. Galster & J. Friedrichs, “The Dialectic of Neighborhood Social Mix: Editors’ Introduction to the Special Issue”, in Housing Studies, 30, (2015), pp. 1–17.

Cfr. R. Chetty & N. Hendren, “The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects*”, in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3), (2018), pp. 1107–1162.

Cfr. B. Flyvbjerg et al., MegaProjects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition (Vol. 17), 2003.

Cfr. B.D. Sommers et al., “Three-Year Impacts Of The Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care And Health Among Low-Income Adults”, in Health Affairs, 6(36), (2017), pp. 1119–1128.